What Are The Broad Varieties Of Change In Relation To Human Agency?

Abstruse

This paper argues that feelings of agency are linked to human well-being through a sequence of adaptive mechanisms that promote human development, once existential conditions become permissive. In the start part, we elaborate on the evolutionary logic of this model and outline why an evolutionary perspective is helpful to understand changes in values that requite feelings of agency greater weight in shaping human well-being. In the second office, we exam the key links in this model with data from the Earth Values Surveys using ecological regressions and multi-level models, covering some eighty societies worldwide. Empirically, we demonstrate testify for the following sequence: (1) in response to widening opportunities of life, people place stronger emphasis on emancipative values, (2) in response to a stronger emphasis on emancipative values, feelings of agency proceeds greater weight in shaping people's life satisfaction, (iii) in response to a greater bear on of agency feelings on life satisfaction, the level of life satisfaction itself rises. Further analyses show that this model is culturally universal because taking into account the forcefulness of a society's western tradition does non render insignificant these adaptive linkages. Precisely because of its universality, this is indeed a 'homo' evolution model in a near full general sense.

Introduction

This paper claims that people tin can and exercise change their strategies to maximize happiness and that changes in value priorities are an inherent part of this process. Furthermore, we claim that in society to understand the logic of these changes, one has to start from an evolutionary model of social modify (Nolan and Lenski 1999; Carneiro 2003; Boyd and Richardson 2005). An evolutionary model recognizes that people adapt their maximization strategies in response to the shifting needs and opportunities of life (Parsons 1964; Dunbar et al. 1999). When these needs and opportunities shift in the same way for many people, this nurtures similar adaptation strategies. Like strategies accumulate to collective trends, which is social alter. Social change of this accumulative blazon is evolutionary in the sense that information technology is cocky-driven: information technology needs no central coordinator with a master plan to merge the adaptations of many people into a commonage trend when the 'invisible hand' of the adaptive logic does the task (Axelrod 1986; Coleman 1990).

Evolutionary dynamics e'er favor what is nigh adaptive under given circumstances (Durham 1991). Both human individuals and societies are adaptive when they command ii types of capabilities: (a) the adequacy to see the needs that accept to be met in order to survive; and (b) the capability to take the opportunities that take to be taken in order to thrive. Among individuals also as societies, the imperative of adjustability puts a premium on 'bureau.' Greater agency involves higher adaptability because for individuals likewise as societies, agency ways the ability to act purposely to their advantage (Bakan 1966; McAdams 1993; Guisinger and Blatt 1994). As Birch and Cobb (1981) outline in The Liberation of Life, one tin run into the evolutionary tendency to increase agency both in the biological evolution of organisms and in the social evolution of civilization. Life evolved from lower to higher organized organisms and this was a move from depression agency, every bit in microbes and insects, to high agency as in primates and above all humans, with the latter being more than empowered to act purposely to their advantage than any other species on world. Civilizations, too, evolved from technologically less to technologically more empowered societies, in a sequence from hunter-gatherer to agrestal to industrial to postindustrial societies, with the latter exerting the most power over their environments (Elias 2004 [1984]; Nolan and Lenski 1999).

In the evolution of life, bureau became about advanced in man beings every bit the species with the highest intellectual power to act with purpose on this planet. As an evolutionary shaped chapters, agency is a particularly 'human' chapters. Information technology is indeed a defining characteristic of our species (Maryanski and Turner 1992). 'Human' evolution is hence any development that promotes the most homo trait—agency (Sen 1999). In the life course of individuals, human development is the maturation of a person's agentic traits. Applying the same logic to the trajectory of societies, all changes that bring a larger number of people in the situation to more fully realize their agentic traits, is to be characterized as 'human' evolution (Welzel et al. 2003).

As nosotros will try to show, variation in life strategies within and betwixt societies reflect evolutionary adaptations to irresolute living weather condition in means that favor agency and hence, homo evolution. And every bit we will run into, as an evolutionary shaped trait, agency is anchored in the human motivational arrangement in that greater feelings of agency yield higher life satisfaction. The rootedness of agency in the human motivational system is, equally we claim, the key driver of human being development. Yet, the way in which bureau is rooted in the human motivational organisation likewise explains why human development does often not proceed. The fundamental reason lies in the fact that the weight with which feelings of agency impact on human being life satisfaction varies with the character of life. When life is a constant threat to suffer, people identify less accent on agency; only when life becomes an opportunity to thrive, exercise people begin to value agency very highly. From a different conceptual angle and with different methodology, the findings of Delhey (2010) on "postmaterialist happiness" betoken to the aforementioned determination as ours.

The commodity is composed every bit follows. In the first part, we debate why an evolutionary perspective is helpful to understand social alter. Specifically, this applies to changes in values that give feelings of agency greater weight in shaping human well-being. In the second part, we test the key links in this model with data from the World Values Surveys using ecological regressions and multi-level models, roofing some lxxx societies worldwide. Empirically, nosotros demonstrate evidence for the following sequence: (1) in response to widening opportunities of life, people place stronger emphasis on emancipative values, (ii) in response to a stronger emphasis on emancipative values, feelings of agency gain greater weight in shaping people's life satisfaction, (3) in response to a greater touch of agency feelings on life satisfaction, the level of life satisfaction itself rises. Further analyses prove that this model is culturally universal because taking into business relationship the strength of a gild'southward western tradition does not return insignificant these adaptive linkages. Precisely because of its universality, this is indeed a 'homo' development model in a most general sense.

Theory

Like everything that is part of life, human societies develop under the evolutionary imperative to adapt to the weather condition of their surround. Otherwise they are non viable (Parsons 1964; Elias (2004 [1984]); Nolan and Lenski 1999; Diamond 2005; Hairdresser 2008). Human societies operate under adaptive pressures equally regards the patterns of (a) how they organize themselves and (b) how they orientate themselves (Dunbar et al. 1999). The first aspect relates to structural adaptability, the second to cultural adaptability. By means of historical experiments, some societies might have constitute patterns of organization and orientation that are meliorate for a society to master given needs and opportunities, making these societies thriving. This creates social models that, once they are recognized as such, tend to diffuse among societies. At some betoken in history, each gild makes distinct choices virtually which model to adopt. 'Evolutionary universals' (Parsons 1964) such as state bureaucracy, market commercialism, the welfare state and balloter democracy diffused in the past because the elites of societies recognized these every bit social models and deliberately chose to adopt them because of their utility (Modelski and Gardner 2002; Meyer et al. 1997). The Prussian Reforms of 1811–1813, the Meiji-Period in Japan and the numerous examples when countries change their political regime or economic order fall into this category.

Social evolution proceeds at different levels. One is the level of societies themselves. Here development proceeds through historical sequences of collective choices exacted by societal elites. This includes choices most wars, international alliances, political regimes, economic orders, and policy programs. Just the imperatives of adaptation operate also on the micro level of individual man beings. Their capacities to exert agency enable them to make choices about what to maximize in their lives. Because these choices are non fully predetermined, they differ. Differences manifest variation in homo maximization strategies. Variation in a puddle of strategies establishes a field of experimentation that filters out what is more useful under what weather. Among perceptive agents this makes learning possible, allowing individuals to chose the strategies they perceive as most useful. When many such micro-level choices are similar, they create a macro-level trend that changes unabridged societies (Boyd and Richardson 2005).

Quite logically, when maximization strategies change, the values that legitimize and inspire these strategies change with them. Value alter can hence be described every bit an evolutionary process that follows Coleman'south (1990) 'bathroom tub model': similar choices at the micro-level create a macro-level trend that changes society. Axelrod (1986), for case, explains changes in societal norms using this adaptive evolutionary logic. And Elias (2004 [1984]) holds that when processes are clearly directed, fifty-fifty though they are neither centrally planned nor coordinated, employing evolutionary logic is the only way to sympathise such processes.

As an evolutionary process, value change involves humans every bit agents who make distinct strategy choices. Agency, understood as the capacity to make purposeful choices, and the learning potential connected to agency, catapult the evolutionary pace of human societies on a new level, accelerating cultural evolution style beyond biological development (Elias (2004 [1984]); Durham 1991; Carneiro 2003).

Nigh theories of value change, including Inglehart's (1977, 1990) generational replacement thesis, follow an evolutionary logic, even if they are not explicit nearly this. This is true for three reasons. Commencement, values are assumed to change in adaptation to changing living conditions. In Inglehart's thinking these are generational adaptations to irresolute living atmospheric condition in people'due south determinative years. Second, the adaptation happens at the micro-level and when many micro-level adaptations move in the same direction, they accumulate to a macro-level trend. Third, these adaptations are not centrally planned or 'socially constructed': no central player controls them. Information technology is the invisible-hand similar logic of adaptation that leads agents who are capable of selection to adopt similar strategies.

The function of values is to inspire maximization strategies that help agents to master two things with which any environment confronts them: needs and opportunities. Coming together needs is necessary to survive. Taking opportunities is helpful to thrive. Like annihilation that is a property of living beings, values operate nether the imperative to respond to the needs and opportunities of their surround. Values inspire maximization strategies and different maximization strategies are differently useful in meeting needs and taking opportunities. Strategies that are not useful in coming together given needs are not viable. They are deselected by the failure of the agents who apply them. With the non-viable strategies, the values that inspire them are deselected likewise. Such negative pick does not crave whatsoever attempt at learning among the involved agents. Information technology always works: anything that is not reality-fit is deselected by reality.

'Negative' choice always reduces the puddle of existing life models to what is viable. Merely even though all existing models in a given pool are viable by definition, some might be more useful than others for thriving. Agents whose values inspire strategies that are more than useful in taking advantage from given opportunities will thrive more than. They will be ameliorate off, which volition become manifest in recognizable signs of success. This sets the stage for 'positive' choice. Positive selection goes beyond deselecting the unviable but it only works in a population of agents whose intellectual capacities empower them to larn from observation and change their deportment and strategies at own will. In a social setting, positive option operates via the markers of success that flag out the thriving agents as role models for others to emulate. Human being societies are unique in their potential for positive choice because they consist of agents who are particularly perceptive of social markers and who have a unique ability to adopt at will what they see as a useful model (Boyd and Richardson 2005).

Still, people's capacity of bureau does by no means fully and freely unfold. Instead, people's agency is socially constrained in manifold ways. Humans grow upwards and alive in stratified societies. Stratification is connected to the vested interests of the powerful. These interests are never openly propagated merely instead are wrapped into legitimizing ideologies whose purpose is to make stratification accepted, particularly amidst those who are at the lower finish. These legitimizing ideologies are made credible and reproduced by another powerful tool that delimits human agency: socialization.

Socialization denotes the processes through which humans are familiarized with what is socially accepted in their society. Refusing to internalize these 'lessons' is socially sanctioned in manifold ways. These sanctions are successful considering humans take evolved every bit social beings who are highly susceptible to group pressures (Tooby and Cosmides 2005). Footnote ane Appropriately, humans internalize most of their values fully unconsciously in an unquestioned process of socialization. Footnote 2 Values are powerful regulators of human behavior because they are office of people's self-construal and identity. The personality aspect of values further limits humans' chapters to freely change and adjust their values (Kluckhohn 1951; Rokeach 1968; Schwartz 2007).

Not enough with that, stratification limits the horizon inside which man agents look for useful office models. A peasant in a feudal society but does not consider a knight as her/his role model because what the knight tin can reach is across the peasant's perceived accomplish. More than generally, stratification locks humans into separated reference groups. The more rigid stratification is, the more is social learning, role model diffusion, and positive selection leap inside narrow reference groups.

All this means that value alter is not coming about easily. Humans practise not unnecessarily experiment with their values because experimentation is costly. It means breaking with given conventions and this involves social sanctions. And yet, humans are not deterministically programmed computers. Stratification, socialization, and the encoding of norms all piece of work to reproduce a society'due south evolved configuration from one generation to the next. And for that to be possible, the private human agents' capacities to change their values at own will has to exist caged (Elias 2004 [1984]; Maryanski and Turner 1992). Still, as much as socialization 'cages' humans' agentic capacities, it does non set them off. In fact, when the surroundings changes and then drastically that it poses new challenges or offers new opportunities, and when the challenges question the viability of old strategies, or when the onetime strategies are no longer useful to take reward of the new opportunities, people's readiness to effort out new strategies increases considerably. Experimentation will climb to new levels. This is to happen well-nigh frequently amid younger people considering for them experimentation is less plush (Flanagan 1987; Inglehart 1997). Having less of a lifetime invested into former values and office models, they tin can more than easily detach their identity from traditional patterns. New lifestyles seek to create their own surroundings in which to thrive and this creates new social milieus. If a variety of such milieus emerges, other people are confronted with a greater diversity of life models to choose from Flanagan and Lee (2001). Since humans are perceptive agents and considering there are recognizable social markers of success, people will figure out which models are most useful in taking reward of new opportunities. Many people will and so adopt the values inspiring these models, resulting in a social diffusion of new values. If this happens, nosotros observe an evolutionary modify of norms, equally described past Axelrod (1986).

An Evolutionary Model of Sequential Adaptive Mechanisms

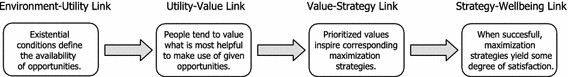

Elaborating on a sequence of adaptations entailed in the human development model of Welzel et al. (2003), Fig. 1 shows an evolutionary sequence of cultural modify, involving iv adaptive links. These links are in a sequential order of ontological priority. Showtime, there is an surround-utility link through which given existential weather define the availability of opportunities to thrive. Existential conditions are all types of environmental weather condition, including not only natural weather condition only too economic, social, and cultural weather. Consider for instance an economic condition: a gild subsists as an agrarian economic system in which a large majority of the population is occupied in nutrient production. Nether this condition, obtaining university-level education is not an easily bachelor opportunity for nearly people because agrarian societies exercise not provide all-encompassing didactics. Even if an individual manages to accomplish a university degree, this is non a very useful opportunity to thrive in agrestal societies because there are few occupations for academically trained people in these types of societies. Instruction is of limited utility under these circumstances. Or consider a cultural status: the norms of a gild favor the male breadwinner model. Obtaining professional training is of limited utility specially for women under this condition. Even if they manage to receive professional training, lack of social acceptance of a female breadwinner would severely limit what women could do with training. Finally, consider a political status: the denial of democratic freedoms, such as the right to vote government out of office. This restriction limits the utility of political information because, if one cannot utilize information to cast a vote that counts, getting information is pretty useless. There are many more examples of how economic, social, cultural and political conditions set limits to opportunities and their utility for people to thrive.

An evolutionary sequence of adaptive links explaining social change

The environs-utility link is followed by a utility-value link: people prioritize the opportunities with the greatest utility in their society, so taking these opportunities becomes a widely supported value. In an agrarian lodge, for case, land belongings is valued. And when a society lacks an efficient pension system so that having many children provides an of import opportunity to subsist in erstwhile age, fertility tends to exist highly valued.

Next follows a value-strategy link: values inspire and legitimize sure maximization strategies. When, for instance, a woman values a life model that favors a double office equally housewife and breadwinner, she is probable to adjust her maximization strategy accordingly. Instead of maximizing the time used for childcare, she volition as well invest time to obtain professional person training.

Finally, there is a strategy-wellbeing link. Every strategy, if successfully realized, is a source of satisfaction. However, we merits that the blazon of strategy has different satisfying potential. Specifically, strategies that are targeted at unfolding agentic traits yield higher levels of satisfaction because they actualize an agentic being's inner traits. In a Maslowian logic (Maslow 1988 [1954]), agency provides the highest level of satisfaction because it meets the nearly uniquely man demand, indeed the demand of highest club in the development of life: cocky-actualization (Veenhoven 2000; Haller and Hadler 2004; Baumeister et al. 2009). As outlined in the Liberation of Life by Birch and Cobb (1981), evolution generally pays a premium on agency because for an individual with greater agency more than things become a useful opportunity. Cocky-actualization is the well-nigh agentic end among all and one of the 'tricks' of evolution to favor agency is to adhere the highest satisfaction yield to self-appearing. Experimental evidence that self-appearing has indeed a high satisfaction payoff is provided in the framework of self-determination theory by Deci and Ryan (2000).

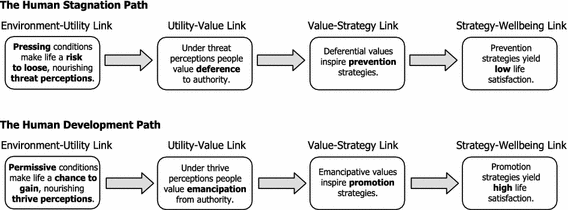

Figure 2 specifies a vicious and a virtuous pathway of this full general sequence of adaptive links, distinguishing them past how inhibitive or favorable they are to man growth, unfolding, and evolution. Appropriately, the brutal pathway is labeled "homo stagnation path" and the virtuous one is labeled "homo development path." They are mirror images of each other.

Vicious and virtuous versions of the evolutionary model of social change

Pressing existential weather condition are found in societies on low levels of economic development. Life in these societies is shorter and harder and offers people less opportunities to thrive. Indeed, under pressing conditions life is a constant hazard to loose, which makes life a constant source of threat perceptions. Threat perceptions lead people to search for shelter nether the shielding roof of authoritatively ordered group life. In this mode, people value deference to group authority. Deferential values in turn inspire and legitimize prevention strategies. This makes prevention of failure people's chronic 'regulatory focus' in society. Footnote 3 If successfully realized, prevention strategies provide relaxation from existential pressures. This is a source of satisfaction but not a very powerful one, for relaxation from pressure leaves the agentic need of actualizing oneself unsatisfied.

Economically advanced societies differ from economically less adult ones in practically all aspects of life. Economically advanced societies are characterized by permissive existential conditions that offer the boilerplate person a longer and more heady life and manifold opportunities to thrive. To take advantage from these opportunities information technology is helpful when people prefer agentic orientations and emancipate themselves from group potency. Emancipative values in turn inspire and legitimize promotion strategies. If successfully realized, promotion strategies provide feelings of fulfillment—the most powerful source of satisfaction.

The key to make the lives of entire populations healthier, longer, richer and more meaningful is economical development (Reinert 2007). The source of economic development is cognition, the basis of all agency (Warsh 2006). In order to thrive, societies have to generate and deploy knowledge and this requires the mobilization of the cognitive potential of the population on equally broad a front as possible (Toffler 1990; Drucker 1993; Florida 2002). Footnote 4 The need to mobilize cognitive potentials broadly makes discriminatory grouping boundaries that bloc certain social groups from opportunities dysfunctional. To get cognitive mobilization started, to keep it going, and to accelerate it, intellectual freedom and equality of opportunities get prime requirements. Thus, cognitive mobilization favors a type of orientation that emphasizes personal autonomy, equality of opportunities, tolerance, and democratic participation. Hence, cerebral mobilization should requite rising to emancipative values that emphasize freedom of expression and equality of opportunities. Inglehart and Welzel (2005) and Welzel (2006, 2007) introduced scales of emancipative values that became known under the label 'self-expression values' considering freedom of expression is one of the core components of these values.

Because cocky-expression values emphasize personal autonomy, people who adopt these values should find the feeling of being agents in shaping their lives more important. And when feelings of bureau get more important in people's life, these feelings should obtain greater weight in shaping people's life satisfaction. Finally, realizing 1's agency potential brings more satisfaction than other satisfying strategies because actualized agency leads to fulfillment—the most highly rewarded type of satisfaction among self-aware, agentic beings.

Operationalization

Hypotheses

Based on these reflections, three hypotheses can exist formulated, each 1 covers one of the in a higher place described adaptive links:

- 1.

There is a utility-values link that ties cocky-expression values to cerebral mobilization.

- 2.

In that location is values-strategy link that ties agentic life strategies to self-expression values.

- 3.

In that location is a strategy-wellbeing link that ties high levels of life satisfaction to agentic life strategies.

Data and Measurements

Our hypotheses propose some rather universal claims that are supposed to operate independent of the type of society under consideration. The very universality of these propositions makes information technology necessary to test them on as broad a footing equally possible. The widest assortment of societies that has ever been covered with questions on values, feelings of agency, and life satisfaction is provided past the European and Earth Values Surveys (henceforth: Values Surveys-VS). The VS accept fielded a standardized questionnaire amid nationally representative samples of residents (sampling between 1,000 and three,000 respondents per state) in more 90 societies on all inhabited continents, representing more than 90% of the world population. We use pooled VS data from rounds Three (1995–1999), 4 (2000–2001), and V (2005–2007), covering a roughly 10 year period from 1995 to 2005. Details on questionnaire wording, fieldwork organisation and data access tin exist obtained at world wide web.worldvaluessurvey.org.

One part of our analytical strategy is to examine how culturally specific or universal the linkages we propose are. From the viewpoint of cultural relativism, 1 might doubtable that self-expression values and feelings of agency are specifically western concepts that do not actually apply to non-western cultures. If this were indeed true, the linkages we propose would not work once i takes into account the forcefulness of a order's Western traditions. The question, withal, is where the strength of a western cultural heritage becomes most manifest. Agreeing with Huntington (1996), nosotros think that one of the nigh distinct societal products of the w is liberal commonwealth. The widely cited work of Acemoglu and Robinson (2006) supports this view. The concept of liberal democracy has been invented and further developed in the westward and exists at that place for the longest time. This is specially for the Protestant Due west, which, according to Max Weber, represents the western liberal spirit well-nigh clearly. From the Protestant West, liberal democracy diffused into other regions in a sequence reflecting these regions' closeness to the west, moving to catholic countries and then to Far Eastern and African countries, being most delayed until today in the Middle East. These cultural differences are perfectly reflected in the length of time since a state has liberal commonwealth.

To measure the endurance of commonwealth, we apply Gerring'due south 'democracy stock' indicator as of 1995 (Gerring et al. 2005). This variable adds up the democracy scores a order has accumulated over time on the Polity 4 autocracy-democracy index (Marshall and Jaggers 2000) just depreciates scores from by years by i% for each twelvemonth they are preceding the reference yr 1995. This index reflects a society'south accumulated experience with liberal democracy with a premium on contempo experience. Footnote 5 For the reasons just outlined, we interpret the democracy stock variable as an indication of the forcefulness of western traditions in a club and characterization information technology accordingly.

To measure how advanced cognitive mobilization is in a society we use the World Bank's "knowledge alphabetize" (KI) as of 1995, which indicates "a society's ability to generate, adopt and, diffuse knowledge. The KI is the simple average of the normalized scores of a social club on the fundamental variables in the 3 knowledge economy pillars: instruction, innovation, and ICT (World Bank 2008)." The noesis index combines data on didactics (using indicators like the tertiary enrollment ratio), on innovation (using indicators like the number of patents per x,000 inhabitants), and on data applied science (using indicators like the number of internet hosts per 1,000 inhabitants). We rescaled the index into a range from 0 to 1.0, with higher values indicating a more advanced knowledge economy. A description of alphabetize construction and data are available for download at: http://info.worldbank.org/etools/kam2/KAM_page5.asp. In the post-obit analyses, nosotros label this variable "cognitive mobilization."

Self-expression values comprise a conglomerate of egalitarian, liberal, democratic and expressive orientations. These orientations cohere more every bit aggregate properties of populations than as personal attributes of individuals because at that place is more variance and co-variance in these orientations between than within populations. Post-obit Welzel (2007) nosotros build a scale of self-expression values from VS data equally shown in Table 1. The scale range is from 0 for someone belongings the least expressive position in each of the iv component orientations to 1.0 for someone holding the nigh expressive position in all of them.

Feelings of agency, ofttimes also chosen locus of control, are covered in the VS by question number V46, which asks: "Some people experience they have completely complimentary choice and control over their lives, while other people feel that what they do has no real effect on what happens to them. Delight use this scale where one ways 'no choice at all' and ten means 'a great bargain of option' to indicate how much freedom of choice and control y'all feel y'all have over the way your life turns out." We recoded responses into a normalized scale with a range from 0 for the least agentic position to 1.0 for the most agentic position.

Life satisfaction is addressed by VS question number V22, which asks: "All things considered, how satisfied are y'all with your life as a whole these days? Using this card on which 1 ways you are 'completely dissatisfied' and x means yous are 'completely satisfied' where would yous put your satisfaction with your life equally a whole?" We normalized life satisfaction into a calibration range from 0 for the least satisfied position to 1.0 for the most satisfied i.

A huge and still growing literature on subjective wellbeing suggests that life satisfaction is influenced by many factors and agency is only i of them (for overviews see Veenhoven 2000; Lykken 2000; Diener et al. 2006). Footnote 6 Fabric factors, such as someone's actual income, but even more so a person's subjective monetary saturation play likewise a office (Diener and Oishi 2000; Inglehart et al. 2008). To include monetary saturation in our consideration is theoretically intriguing considering its materialist nature brings budgetary saturation into a stark dissimilarity to agency feelings as a more idealistic source of satisfaction. To measure subjective monetary saturation nosotros use question number V68 of the VS, asking: "How satisfied are you lot with the financial situation of your household? Please use this card over again to help with your reply." The show card depicts a 1–10 scale which we transformed into a normalized scale range from 0 for the least satisfied position to 1.0 for the most satisfied one.

Another satisfying cistron that is often brought into contrast to agency is 'communion' (Bakan 1966; McAdams 1993; Guisinger and Blatt 1994). Thus, we exam the possibility that agentic life strategies and communal life strategies are contradictory. To measure communion, we construct a composite index that combines people's accent on the family and friends as important life domains, using VS questions V4 and V5, in which people are asked to bespeak the level of importance they ascribe to the family (V4) and friends (V5) on a 4-bespeak scale from "not at all important" to "very of import." We average both importance levels into a scale from 0 for someone attributing no importance to both family unit and friends to 1.0 for someone attributing high importance to both. We interpret this calibration as measuring people's communion emphasis. We will also utilize standard demographic controls to make sure that the furnishings of our potentially satisfying factors are not confounded by sex, age, income and education. Footnote 7

Based on the data and variables just described we test our three hypotheses on the societal-level and the individual level. At both levels of assay, the questions nosotros try to answer are (1) whether units of observation that are more avant-garde in cognitive mobilization are besides more than advanced in cocky-expression values, (2) whether units of ascertainment that are more advanced in cocky-expression values follow a more than agentic life strategy, and (3) whether units of observation driven by a more agentic life strategy reach higher levels of life satisfaction.

Findings

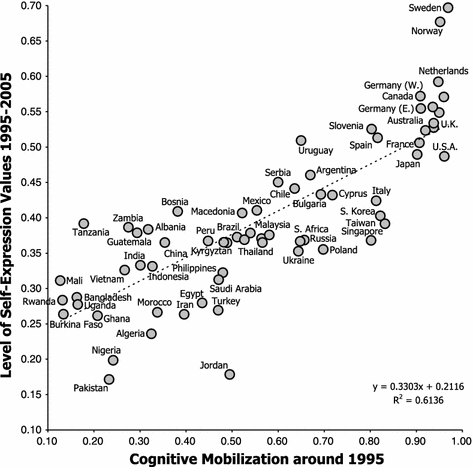

Tabular array 2 shows the result of regressions when entire societies are the unit of analysis. The table analyzes a society's base of operations level of self-expression values as a function of cognitive mobilization and western traditions. Considered separately, both western traditions and cognitive mobilization influence a social club'south base level of cocky-expression values positively: societies with stronger western traditions and cognitively mobilized societies exhibit higher base levels of self-expression values. Nether mutual controls, notwithstanding, it turns out that the self-expression issue of cerebral mobilization outperforms that of western traditions. Thus, the outcome of cognitive mobilization is not contingent on western traditions: fifty-fifty asunder from these traditions does cerebral mobilization nurture cocky-expression values. In other words, cognitively mobilized societies are not more than self-expressive because they take stronger western traditions but considering they are cognitively mobilized. The scatterplot in Fig. 3 visualizes the utility-values link that ties self-expression values to cognitive mobilization.

An analogy of the utility-value link

In social science there is always the possibility of the 'ecological fallacy,' which means to mistakenly infer from macro-level linkages that the same linkages be at the micro-level (Robinson 1950; Alker 1969). Indeed many linkages that explicate differences between societies may not explain differences between individuals within societies (Przeworski and Teune 1970). In this case, the macro-level linkages are ecological artifacts of aggregation because they take no micro-foundation.

Table 3 examines the micro-foundation of the utility-value link, using a multi-level model, often also referred to as a 'hierarchical linear model' (Bryk and Raudenbush 2002). The coefficients of the societal-level component of the model are not exactly identical to those in the ecological regression models because missing data on some individual-level variables reduce the sample from 83 to 78 societies. Still, we detect cognitive mobilization to heighten the base level of self-expression values in a society more than double equally much as western traditions do. Looking at the individual-level findings, the model provides a nice analogy of the utility logic. Education offers people greater opportunities to thrive almost everywhere and so education should accept a universally positive upshot on self-expression values, irrespective of societal-level conditions. This is indeed what we observe: i's level of education shows a more often than not positive and highly significant event on i'south self-expression values, even taking societal-level variation of this outcome into account. Yet, the size of education's self-expression issue is partially chastened by cognitive mobilization at the societal-level: even though the consequence of educational activity is always positive, it tends to be bigger in cognitively mobilized societies. This makes sense in the utility logic: in cognitive mobilized societies, a larger number and greater variety of occupations and activities is available in which didactics pays off, and so instruction offers greater thriving opportunities in cognitively mobilized societies. Education has greater utility for personal growth in cognitively mobilized societies, which is reflected in a stronger outcome on self-expression values in such societies.

What about the values-strategy link that is supposed to tie agentic life strategies to self-expression values? We understand agentic life strategies as a matter of degree: it is the relative weight that feelings of agency have in shaping people'due south life satisfaction. To measure this weight, we calculate for each society the average strength by which people'due south feelings of bureau affect on their life satisfaction, which becomes manifest in the magnitude of the coefficient that regresses life satisfaction on agency feelings. However, we are interested in the relative weight of feelings agency, as compared to the well-being outcome of monetary saturation whose materialist nature sets it in stark dissimilarity to such an idealistic aspect every bit bureau. Thus, nosotros calculate for each gild how much stronger or weaker people's life satisfaction is shaped by agency feelings than by monetary saturation, subtracting the well-being effect of budgetary saturation from that of agency feelings. In other words, we count the monetary against the agentic wellbeing effects and average these differences over entire populations. This measures per guild the relative force of agentic life strategies, which is the dependent variable in Table four.

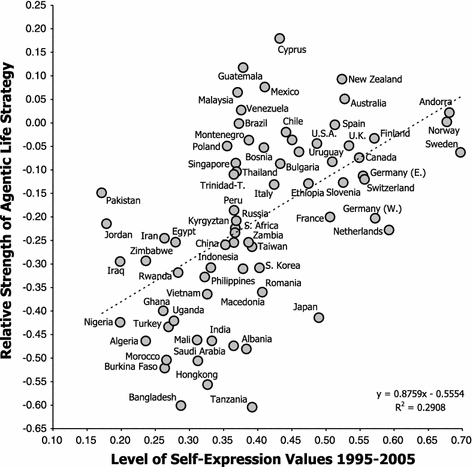

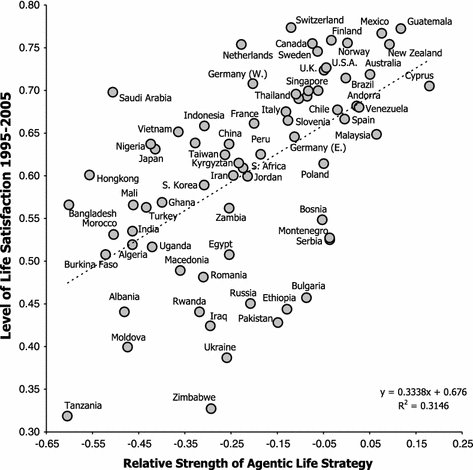

The regression results in Table four show the value-strategy link that is supposed to tie agentic life strategies to self-expression values. This link is positive and highly significant and information technology does not suspension down nether control of western traditions. It is past no means so that agentic life strategies are tied to self-expression values only in western societies, as cultural relativists might doubtable. Put differently, agentic life strategies are non stronger in cocky-expressive societies because these societies are more than western but because they are more cocky-expressive. A visual illustration of the value-strategy link is provided by the scatterplot in Fig. 4.

An analogy of the value-strategy link

As with the utility-value link, the value-strategy link has a micro-foundation too, and quite in a Maslowian sense. For this matter consider that we can calculate for each individual the residual in life satisfaction that is unexplained by this private's agency feeling. This tells us how much a person'south satisfaction is unrelated to bureau, which is a straight inverse indicator of agency-driven satisfaction, that is, agentic life strategies. At present judge what is the all-time private-level predictor of someone's agentic life strategy? The reply is monetary saturation. Among those respondents in VS 3 to Five whose life satisfaction falls brusque of what their agency feelings predict (North = 112,487), monetary satisfaction reduces the extent to which life satisfaction falls short of agency feelings in highly significant ways. Specifically, a one unit of measurement increment in monetary saturation decreases the extent to which life satisfaction falls short of agency past .26 units on a calibration range from −1.0 to +1.0. This reduction operates in a conviction interval between .25 and .27 units and explains xiii.7% of the total variation in agentic life strategies (or their inverse, to be more precise). Counting out from this relationship the variation that is located between societies, a 1 unit of measurement increment in budgetary saturation reduces the extent to which life satisfaction falls short of agency by .24 units, operating in a conviction interval between .244 and .235 units, notwithstanding accounting for ten.2% of the total variation in agentic life strategies. Hence, material needs must be satisfied offset before agency tin can go the driver of life satisfaction.

Let us now consider the strategy-wellbeing link that is supposed to tie the level of life satisfaction to the strength of agentic life strategies. The regression analyses in Table 5 and the scatterplot in Fig. five certificate that this link, too, is statistically significant, operates in the expected direction, and does not vanish when one takes the forcefulness of a society's western tradition into business relationship. Thus, when more people in a society follow agentic life strategies, this society's base of operations alive satisfaction level tends to exist higher. And this human relationship does not exist because societies with stronger western traditions nurture both agentic life strategies and high levels of life satisfaction. These findings seem to betoken that even though diverse maximization strategies yield some level of satisfaction, certain strategies yield more than than others. Specifically, agentic strategies yield particularly high rates of life satisfaction.

An analogy of the strategy-wellbeing link

Table vi shows a multi-level model that examines the micro-foundation of the strategy-wellbeing link. The societal-level component of the multi-level model corresponds to the findings that nosotros have seen in the ecological regressions, so the novelty is in the individual-level component. Here we test the relative touch on of three maximization strategies on people's life satisfaction, including (a) a communal strategy driven by communion emphasis, (b) a monetary strategy driven past monetary saturation, and (c) an agentic strategy driven past agency feelings. We are not simply interested in the relative size of these strategies' general effects but likewise whether and in what direction these effects are moderated past societal-level characteristics.

Patently, each strategy contributes significantly and positively to life satisfaction and this is more often than not so, even taking societal-level moderations into business relationship. Generally, budgetary saturation shows the strongest, agency feelings the second strongest, and communion accent the third strongest effect on life satisfaction. In contrast to what much of the psychological literature assumes (just run across Baumeister et al. 2009), agency feelings and communion emphasis are in no merchandise-off relation every bit strategies to maximize life satisfaction. Otherwise, their interaction should exist significantly negative. In fact, still, it is significantly positive: agency feelings and communion emphasis amplify each others' impact on life satisfaction. But both strategies collaborate negatively with monetary saturation, which indicates a trade-off relation: a decreasing impact of monetary saturation on life satisfaction amplifies the wellbeing effects of bureau and communion, and vice versa. Looking at moderations, the wellbeing effect of communion does not seem to vary with societal-level characteristics but the furnishings of saturation and agency exercise, and they do and then in a opposite way. When many people in a society follow an agentic satisfaction strategy, an individual yields much less satisfaction from more than monetary saturation and more satisfaction from stronger agency feelings. The positive moderation of agency'south individual-level issue by the prevalence of agentic strategies at the societal-level illustrates a confirmation mechanism known as 'social proof' in psychology (Cialdini 1993): when many people in a social club follow agentic strategies one feels confirmed when one does so oneself, which increases bureau'southward satisfaction payoff.

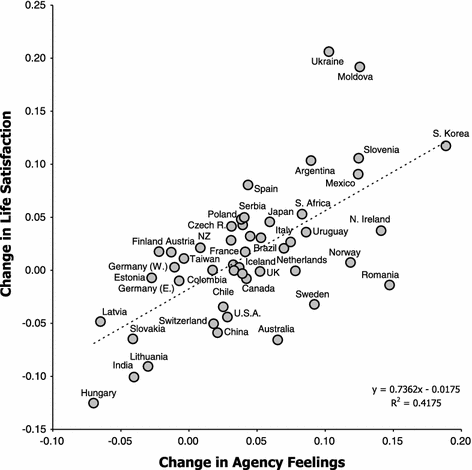

In a dynamic perspective, our findings imply that rising feelings of agency bring ascent levels of life satisfaction. The bear witness in Fig. 6 confirms this expectation. The graphic shows the extent and management in which societies experienced changes in their overall feelings of agency and in life satisfaction from the primeval to the latest available survey in the VS. We circumscribe ourselves to changes that stretch over at least iii rounds of the VS, which implies a minimum temporal distance of 15 years. It is clear that changes in agency feelings correspond with changes in life satisfaction. Controlling the initial level of life satisfaction that was given correct at the beginning of the changes depicted here does not diminish the human relationship.

Changes in agency feelings and life satisfaction

Word

This article provided evidence for an evolutionary sequence of adaptive linkages that anchor agency in the homo motivational system. Commencement, there is utility-value link through which people learn to value the opportunities that accept near utility under given existential conditions. The logic of this link ties the ascension of self-expression values to the thriving opportunities that emerge with the cognitive mobilization of societies. Second, there is a value-strategy link through which people translate their values into corresponding maximization strategies. This link ties the ascension of agentic maximization strategies to the emergence of cocky-expression values. 3rd, there is a strategy-wellbeing link that gives different maximization strategies a differential satisfaction yield, in line with a Maslowian logic due to which self-actualizing strategies yield the most satisfaction. This link ties high levels of life satisfaction to agentic maximization strategies.

Nosotros see the forcefulness of our evidence in its spatial telescopic and generality. We used representative information that can be generalized to entire national populations and nosotros covered a wide, indeed global, range of societies at different levels of economical development and of very different cultural roots. Insofar we tin can say that the evidence for the adaptive links we have been showing is indeed wide and general. Also, we could show that the adaptive links operate at different levels of analyses and that what nosotros saw at the macro-level of societies has a micro foundation among individuals. This further speaks to the validity of our findings.

However, there is ane serious limitation. Our evidence is mostly cross-sectional and lacks a more extended longitudinal component. In lack of extensive longitudinal data it is impossible to sort out what came showtime and what followed, and and so causality cannot be fixed. Without the means to test causality empirically, the causal direction in a proven relationship remains a matter of theoretical plausibility. Here we recall we provide a model that allows for some plausible causal interpretations that can be tested in the future. For this to become possible, more than longitudinal data must become available, even though some supportive evidence is available already now. Specifically, Inglehart et al. (2008) have shown that ascent levels of happiness over the past 20 years in some l societies are related to an increasing sense of freedom, which in plough is related to rise self-expression values. Yet, these authors merely report findings, without situating them in a broader theoretical framework from which to derive concise sets of testable hypotheses. The human being development framework provided hither does codify such sets of hypotheses and showed some commencement confirmatory testify. This testify seems broad and deep enough to serve as a starting signal for farther longitudinal and experimental studies into the links proposed hither.

Notes

-

Responsiveness to conformity pressures can lead to the adoption of behavior that is socially adaptive because information technology avoids sanctions merely which is harmful for the well-existence of the individual and even an entire society. Societies whose conformity pressures crusade harmful behavior are themselves maladaptive, which in the farthermost case can pb to their "Collapse" (Diamond 2005).

-

Often, people develop rational arguments to legitimize their values. But the values have not been chosen on the basis of logical reasoning. Rather, rationality is constructed to justify a priori internalized values.

-

The distinction between a prevention and a promotion focus in regulatory focus theory is normally applied to variation in conditions between different brusk-term situations (Foerster et al. 1998). But the same logic can be applied to variation in conditions betwixt different long-term conditions.

-

There is no ultimately accepted definition of 'cognitive mobilization' but the most ofttimes used sources are Inglehart's Civilization Shift (1990) and Dalton's Denizen Politics (2006), both of which emphasize informational resource and intellectual skills as the ii components of cognitive mobilization. For example, Dalton (2006:19) defines cognitive mobilization as a process through which more people learn "the political resources and skills that prepare them to bargain with the complexities of politics and reach their own decisions." Political resources and skills are understood here as informational resource and intellectual skills. The expansion of informational resource is related to the rise, spread, and reach of modern electronic mass media and information applied science, while the increment and spread of intellectual skills is linked to rise levels of education and cognitive demands in mod occupations. The link to the core features of knowledge societies is thus obvious. Understanding the complexities of politics can certainly be extended to agreement the complexities of modern life in general and the term "attain their own decisions" makes the connection to bureau obvious.

-

We thank John Gerring for his generosity in sharing his information with the states.

-

Farther readings include Peterson et al. (2005), Hagerty and Veenhoven (2006).

-

Biological sex activity is measured in V235 of the VS past observation of the interviewer. We coded female sexual practice as ane.0 and male sex activity as 0. The age measure out is taken from V237 of the VS and measures biological age in years. Household income is measured in V253 on a scale of 1 to ten for national income brackets. Nosotros transformed this into a normalized scale with minimum 0 for the everyman and ane.0 for the highest income bracket. Level of pedagogy is measured in V238 on a 9-signal calibration from i for no education whatsoever to 9 for a university caste. We transformed this into a normalized calibration with minimum 0 for the lowest level and 1.0 for the highest level of educational activity.

References

-

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2006). Social origins of democracy and dictatorship. New York: Cambridge University Press.

-

Alker, H. R., Jr. (1969). A typology of ecological fallacies. In M. Dogan & S. Rokkan (Eds.), Quantitative ecological analysis in the social sciences (pp. 69–86). Cambridge: MIT.

-

Axelrod, R. (1986). An evolutionary approach to norms. American Political Scientific discipline Review, 80, 1095–1111.

-

Bakan, D. (1966). The duality of human beingness: An essay on psychology and faith. Boston: Beacon.

-

Barber, North. (2008). Evolutionary explanations for societal differences and historical change. Cross-Cultural Research, 41, 123–148.

-

Baumeister, R. F., Masicampo, Eastward. J., & DeWall, C. N. (2009). Prosocial benefits of feeling gratuitous. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 260–268.

-

Birch, C., & Cobb, J. B., Jr. (1981). The liberation of life: From the prison cell to the community. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

-

Boyd, R., & Richardson, P. J. (2005). How microevolutionary processes give ascent to history. In R. Boyd & P. J. Richardson (Eds.), The origin and evolution of cultures (pp. 287–309). New York: Oxford University Press.

-

Bryk, A., & Raudenbush, S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

-

Carneiro, R. (2003). Evolutionism in cultural anthropology. Boulder: Westview.

-

Cialdini, R. B. (1993). Influence: Scientific discipline and practise. New York: Harper Collins.

-

Coleman, J. South. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge: Harvard University Printing.

-

Dalton, R. J. (2006). Citizen politics. Washington, DC: PQ Press.

-

Deci, E. Fifty., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The what and why of goal pursuits: Homo needs and the cocky-decision of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, xi, 227–268.

-

Delhey, J. (2010). From textile to postmaterial happiness? National abundance and determinants of life satisfaction in cantankerous-national perspective. World Values Research, 2, thirty–54.

-

Diamond, J. (2005). Collapse: How societies chose to fail or succeed. New York: Viking.

-

Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Scollon, C. N. (2006). Beyond the hedonic treadmill: Revising the adaptation theory of well-being. American Psychologist, 61, 305–314.

-

Diener, E., & Oishi, S. (2000). Money and happiness: Income and subjective well-being across nations. In E. Diener & E. Suh (Eds.), Subjective well-being across cultures. Cambridge: MIT.

-

Drucker, P. (1993). Post-capitalist society. New York: Harper Collins.

-

Dunbar, R., Knight, C., & Power, C. (1999). An evolutionary approach to human culture. In R. Dunbar, C. Knight, & C. Power (Eds.), The evolution of culture (pp. 1–xiv). New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

-

Durham, W. H. (1991). Coevolution: Genes, culture, and homo variety. Stanford: Stanford Academy Press.

-

Elias, N. (2004). Knowledge and power: An interview by Peter Ludes. In North. Stehr & V. Meja (Eds.), Order & cognition (pp. 203–242). New Brunswick: Transaction. [1984].

-

Flanagan, Southward. (1987). Value change in industrial society. American Political Science Review, 81, 1303–1319.

-

Flanagan, S., & Lee, A.-R. (2001). Value change and democratic reform in Japan and Korea. Comparative Political Studies, 33, 626–659.

-

Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative form. New York: Basic Books.

-

Foerster, J., Higgins, E., & Idson, L. (1998). Approach and abstention strength during goal attainment: Regulatory focus and the 'goal looms larger' effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1115–1131.

-

Gerring, J., Bond, P., Barndt, West. T., & Moreno, C. (2005). Democracy and economic growth. Globe Politics, 57, 323–364.

-

Guisinger, Due south., & Blatt, Southward. (1994). Individuality and relatedness. American Psychologist, 49, 104–111.

-

Hagerty, Yard., & Veenhoven, R. (2006). Ascent happiness in nations, 1946–2004. A reply to Easterlin. Social Indicators Research, 79, 421–436.

-

Haller, Chiliad., & Hadler, One thousand. (2004). Happiness equally an expression of freedom and self-determination: A comparative multilevel analysis. In W. Glatzer, S. von Below, & M. Stoffregen (Eds.), Challenges for quality of life in the contemporary world. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

-

Huntington, S. P. (1996). The clash of civilizations and the remaking of the world order. New York: Simon & Schuster.

-

Inglehart, R. (1977). The silent revolution. Princeton: Princeton University Printing.

-

Inglehart, R. (1990). Civilisation shift in advanced industrial societies. Princeton: Princeton Academy Printing.

-

Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization and postmodernization: Cultural, economic and political change in 43 societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

-

Inglehart, R., Foa, R., Peterson, C., & Welzel, C. (2008). Development, freedom, and rising happiness. Perspective on Psychological Science, three, 264–285.

-

Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, cultural change and democracy: The human evolution sequence. New York: Cambridge University Press.

-

Kluckhohn, C. (1951). Value and value orientation in the theory of action. In T. Parsons & Due east. Shils (Eds.), Towards a general theory of action. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

-

Lykken, D. (2000). Happiness, the nature and nurture of joy and contentment. New York: St. Martin'south Griffin.

-

Marshall, M. G., & Jaggers, K. (2000). Polity IV project (information users manual). College Park: Academy of Maryland.

-

Maryanski, A., & Turner, J. H. (1992). The social cage: Human nature and the development of club. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

-

Maslow, A. (1988). Motivation and personality (3rd ed.). New York: Harper & Row. [1954].

-

McAdams, D. P. (1993). The stories we live by. New York: Harper Collins.

-

Meyer, J. West., Boli, J., Thomas, Thou. M., & Ramirez, F. O. (1997). Globe guild and the nation-state. American Journal of Folklore, 103, 144–181.

-

Modelski, Chiliad., & Gardner, P. (2002). Democratization in long perspective. Technological Forecasting and Social Modify, 69, 359–376.

-

Nolan, P., & Lenski, G. (1999). Homo societies (8th ed.). New York: McGraw Hill.

-

Parsons, T. (1964). Evolutionary universals in club. American Sociological Review, 29, 339–357.

-

Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, One thousand. E. P. (2005). Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The total life versus the empty life. Journal of Happiness Studies, half dozen, 25–41.

-

Przeworski, A., & Teune, H. (1970). The logic of comparative social inquiry. New York: Wiley.

-

Reinert, East. S. (2007). How rich countries got rich … and why poor countries stay poor. New York: Carroll & Graf.

-

Robinson, Westward. Southward. (1950). Ecological correlations and the beliefs of individuals. American Sociological Review, xv, 351–357.

-

Rokeach, 1000. (1968). Behavior, attitudes and values. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

-

Schwartz, S. H. (2007). Value orientations: Measurement, antecedents and consequences beyond nations. In R. Jowell, C. Roberts, R. Fitzgerald, & G. Eva (Eds.), Measuring attitudes cantankerous-nationally (pp. 161–193). London: Sage.

-

Sen, A. (1999). Evolution equally liberty. New York: Alfred Knopf.

-

Toffler, A. (1990). Power shift: Knowledge, wealth and violence at the edge of the 21 st century. New York: Bantham.

-

Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (2005). Evolutionary psychology: Conceptual foundations. In D. M. Kiss (Ed.), Evolutionary psychology handbook. New York: Wiley.

-

Veenhoven, R. (2000). Freedom and happiness: A comparative study in xl-4 nations in the early 1990s. In E. Diener & E. Suh (Eds.), Subjective well-being across cultures (pp. 257–288). Cambridge: MIT.

-

Warsh, D. (2006). Knowledge and the wealth of nations. New York: W.W. Norton.

-

Welzel, C. (2006). Democratization every bit an emancipative procedure. European Journal of Political Research, 45, 871–896.

-

Welzel, C. (2007). Practice levels of democracy depend on mass attitudes? International Political Scientific discipline Review, 28, 397–424.

-

Welzel, C., Inglehart, R., & Klingemann, H. D. (2003). The theory of human development: A cantankerous-cultural assay. European Periodical of Political Research, 42, 341–379.

Open Admission

This commodity is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial employ, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided the original writer(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial utilize, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(due south) and source are credited.

Reprints and Permissions

Nearly this article

Cite this article

Welzel, C., Inglehart, R. Bureau, Values, and Well-Being: A Human Development Model. Soc Indic Res 97, 43–63 (2010). https://doi.org/x.1007/s11205-009-9557-z

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Effect Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1007/s11205-009-9557-z

Keywords

- Bureau feelings

- Cultural evolution

- Emancipative values

- Homo development

- Knowledge economies

- Life satisfaction

- Well-being

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11205-009-9557-z

Posted by: smithdidess1938.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Are The Broad Varieties Of Change In Relation To Human Agency?"

Post a Comment